Cairo

This series examines racial and geographic circumstances surrounding the city of Cairo, Illinois.

PROJECT STATEMENT

The fertile land surrounding the rivers was called Little Egypt because of its similarity to the Nile River Valley, and Cairo, the queen of Little Egypt, was the center of activity.

This series examines racial and geographic circumstances surrounding the city of Cairo, Illinois. Located at the extreme southern tip of the state, at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, Cairo’s unique geographic location brought the city to prominence in the 1860’s. While steamboats were the principal mode of transporting goods, the city was a vital hub. Cairo’s location served as a critical link in the Underground Railroad and was a strategic port during the Civil War. The city’s status declined as diesel trains, steel hulled barges, and bridges negated Cairo’s importance leaving it one of the poorest cities in the state.

Illinois’ status as a Northern state did not prevent racial polarization from taking root. In fact, Cairo maintained much of the climate and character of the South–paternalistic and segregationist–despite a historically large African-American population. Racial intolerance and injustice were rampant throughout the 20th century. In 1909, the public lynching and brutal mutilation of William James, a young black man, for the alleged murder of a young white woman was committed by a mob of 10,000 Cairo citizens. Attempts to desegregate in the 1950’s were met with violence and intensified discriminatory policies. In 1963, a newly built public swimming pool was closed rather than integrate—the pool was filled with cement and never reopened. As in Newark and Detroit, 1967 was a breaking point, prompted by the killing of Robert L. Hunt Jr., a 19-year-old who died while in police custody. Officers claim Hunt committed suicide, though evidence indicates he was murdered. Between 1969 and 1972, shooting and arson were almost daily occurrences in Cairo.

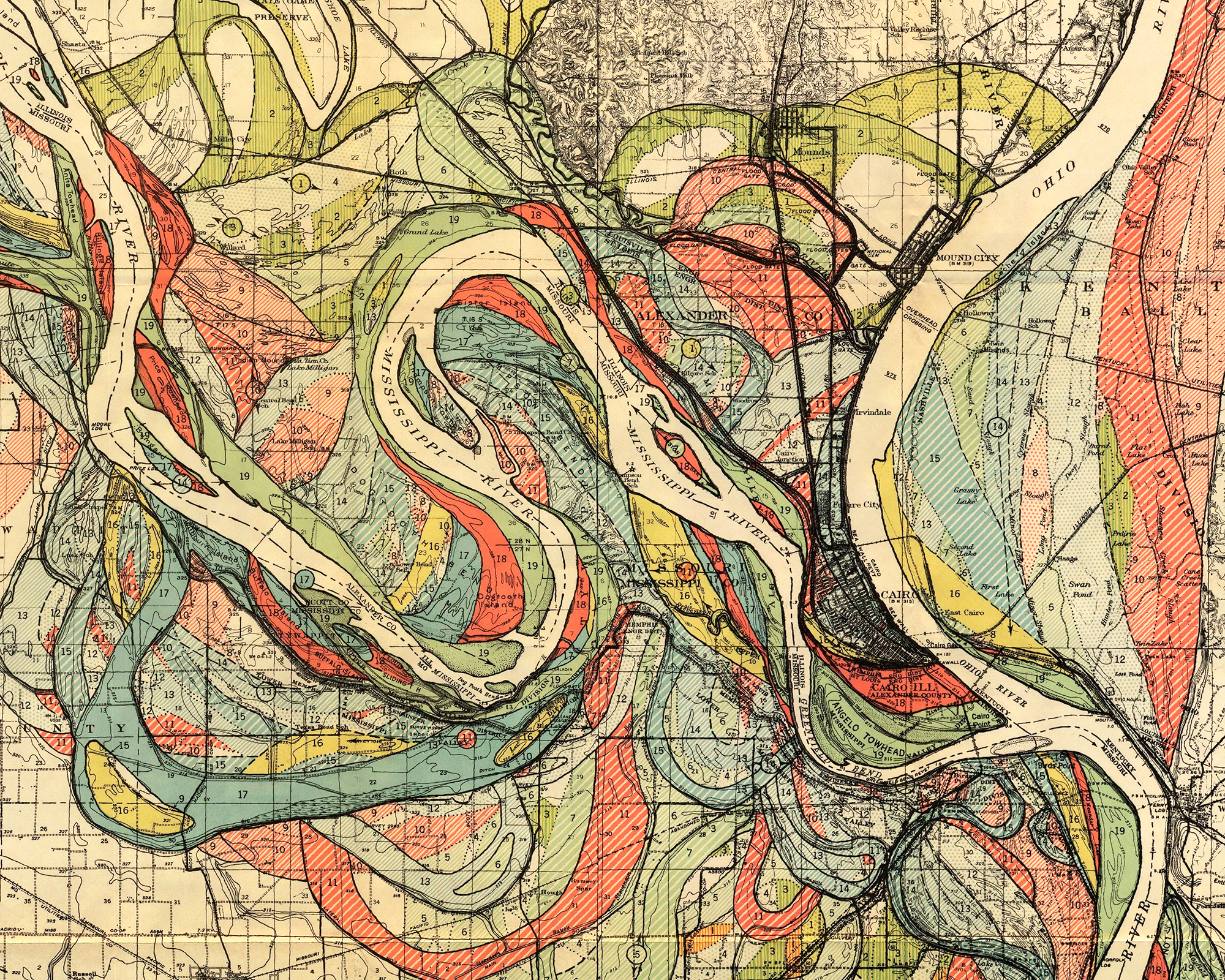

Literary and historical materials were my means of understanding Cairo’s tumultuous past and a departure point for documentation. A 1973 U.S. Commission on Civil Rights report and Harold Fisk’s 1944 geographic renderings of the Mississippi River valley brought to light the city’s brutal racial hatred and the unpredictable force of the Mississippi River. Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad and Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn–one contentious, the other subversive–supported my investigations.